The objective of this post is to discuss some concepts related to the field of memetics. It was inspired by reading Antimemetics: Why Some Ideas Resist Spreading by Nadia Asparouhova.

Intro

Others and I share the impression that we are witnessing the emergence of a new field. While memetics were introduced by Richard Dawkins in 1976, and they were studied intensively during the 1990s and early 2000s, it died shortly after due to inability to agree on basic definitions and how to do empirical research. At this point in time, the context around the field has changed so much 1 that it feels like a whole new discipline (though there is still a lot to learn from back then).

Bringing the study of memetics more into the public is something I’m quite interested in, as I referenced in a previous post (On the growing importance of cogsec). As our societies progress, the flow of information and ideas will increase substantially, as well as the (economic) value associated with it. The incentives might not be in the correct places for private and public entities (they certainly are not right now) and this can lead to catastrophic consequences. Early exposure to the mechanisms of how ideas spread can help alleviate this.

The book, while short, succeeds in putting into print a lot of the principles of the contemporary study of memetics. It is part of the The Dark Forest Collective published pieces. They are a group of internet writers who focus on how people are moving away from public online spaces toward more private, safer, and context-rich one, denominated “dark forests”, as a response to adversarial dynamics on the public web. I really appreciate their work, though sometimes you do realize that they are not really young and how that shapes their view. They try, but they don’t really “get it” the same way a digital native does, though I must admit lately I’m feeling a bit like that too.

History

Dual inheritance theory proposes to explain human behavior as the product of two evolutionary processes, genetic evolution and cultural evolution 2, that interact in a feedback loop.

Memetics is the study of how memes (units of cultural information like ideas or behaviors, anything that can be passed on via social learning) are transmitted, replicated, and evolve within a culture. It’s a lens for studying cultural evolution, putting emphasis on the ability (or inability) to capture attention. Human attention (not the other one) is a scarce resource, making the spread of memes limited and forcing them to adapt to changing environments to survive, setting the stage for a evolutionary process to happen.

Comparing cultural to biological evolution (memes to genes) is not a great research direction, as we’ll see later, but it can be useful in some contexts. Biology studies the patterns of matter that survive, whereas memetics studies patterns of behavior that survive. Memes generally work as symbionts with human hosts, and evolve ways of embedding in & transmitting between them. The coevolution of genes and memes also plays a crucial role, as they balance each other out in interesting ways.

Memetics has a complicated history, since it’s such an abstract topic, the terminology and writing is all over the place. Researching this felt quite similar to my dive into Cybernetics. Both emerged from interdisciplinary roots, struggled with ontological debates and fell from grace with the mainstream. Both focus on systems, feedback loops, and information (the spread f a meme is a classic positive feedback loop). You could frame memetics as a subfield of cybernetics. They are also common words in schizoposting.

In here I’ll focus on memetics as a science, though many philosophers have been talking about it for quite some time. This section is not exhaustive, I’ll mention some people and ideas that caught my attention, but for a more complete walkthrough check out this posts by Tim Tyler (until 2012), Agner Fog (until 1999) and Susan Blackmore. While many of their ideas seem obsolete as of current times, they remain very quite insightful.

Darwin seemed to show some understanding of cultural evolution in the context of language (The Origin of Species, 1859). Other early approaches include The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1896), but the field remained mostly underground until the publication of ‘The Selfish Gene’ (1976) by Richard Dawkins, that dedicated a chapter to this topic and coined the term meme.

The 80s and 90s started seeing some early developments in it’s theoretical foundation. It went through a bit of a golden age with the launch of the Journal of Memetics (1997–2005), that was home to much of the research in this period. Susan Blackmore’s The Meme Machine (1999) was one of the most influential writings, advancing on the ideas of Dawkins. During the 2000s there was a period of decline, as outlined by Bruce Edmonds in an essay where he explained the issues that led to the journal’s cessation: absence of consensus, over-reliance on biological metaphors, reductionism and lack of empirical research due to difficulty. A 2020 analysis comparing the rise and decline of memetics with the relative success of gene-culture coevolution theory blames the fixation on using discrete units of selection (that would allow it to be compared to the biological gene) and excessive emphasis on ontology over hypothesis testing.

This downward period coincided with the surge of memes in popular culture as the internet got introduced to the public. I believe that the most advance research in memetics is currently done by tech giants, political organizations and the militarybehind closed doors 3, as the The War for Attention rages on quietly. In The Case Against Marketing I showed how it’s nothing more than the art of hijacking attention, and how it has been the main source of cultural evolution for quite some time. Most social sciences also interacts with the field constantly, but it is rarely acknowledged. Limor Shifman’s book _Memes in Digital Culture_ (2013) redefined the term, departing significantly from Dawkins’ original by limiting it to only memes in the digital world. Since Shifman’s reformulated, academic research on memes resurged slightly, but with a much narrower scope. LLMs are starting to allow for much more in depth analysis of multimodal domains, most of it focused on hate speech, misinformation and crises.

Interestingly some academics try to distance themselves as much as possible from the term “memetics”. Researchers like Boyd and Richerson’s work in cultural evolution is quite successful, but they use terms like ‘cultural variant’ to avoid comparisons to biology and put much more emphasis on the gene-meme coevolution. In general they are a watered-down version of memetics with less emphasis on Darwinian theory and symbiosis. They seem to have gotten the empirical testing part right though.

In my opinion most of the interesting work is being done outside academic structures. Initiatives like the Open Research Institute are bringing research into the public, though they are still quite early. Their members have some of my favorite posts on the subject, that serve as a great introduction point. I will leave links to interesting people and content on the resources section at the end, but I want to highlight the open-memetics-institute and X community as some of the most vibrant places around.

Categories and Attributes

A useful way of understanding memetics is as a graph, where nodes are the entities that can receive memes and choose to transmit them, and the edges the connections between them. In here we can introduce concepts like degree (number of edges it has), immunity (nodes in a network that are resistant to infection), transmission rate (probability that an infected node will successfully spread an idea to its edges (connections) ), symptomatic period (how long an infected node actively “expresses” the idea); in the memes we have Fidelity (how accurately it reproduces), Fecundity (the speed and volume of its replication) and Longevity (how long it persists).

A node typically goes through 4 phases when getting infected, assimilation, retention, expression and transmission. At each of these stages there is some amount of selection going on, meaning that some memes will disappear from the node. Borrowing from epidemiology, the basic reproduction number is the expected number of cases directly generated by one case in a population where all individuals are susceptible to infection. There are some funny attempts at expressing all of this mathematically, comparing it to infectious diseases, but I don’t give much credence to them.

In Kevin Simler’s essay Going Critical there are a bunch of great interactive visualizers for the above. There he also present the following idea:

there’s a precise tipping point that separates subcritical networks (those fated for extinction) from supercritical networks (those that are capable of never-ending growth). This tipping point is called the critical threshold, and it’s a pretty general feature of diffusion processes on regular networks.

Memeplexes are group of memes that are typically present in the same node, like a particular aesthetic or ideology. It’s also useful to differentiate them based on the realm the exist. A memotype is the form of the meme in an individual’s mind, a mediotype is the physical medium or representation (text, image, etc.) and a sociotype is the distribution of a meme within groups or communities.

Nadia also proposes a way of categorizing memes according to their transmissibility and impact (derived from the previous attributes):

I had a notion of what an antimeme was from qntm’s There Is No Antimemetics Division, and turns out that it was a big inspiration for the book. In fact, I was already aware of most the people and ideas discussed in the book (including qntm’s work) as the author seems to frequent a quite similar internet to me. The citations pages at the end felt eerily alike my bookmarks.

Antimemes involve ideas that resist being remembered, comprehended, or engaged with, despite their significance. When a person encounters an antimemetic idea, there’s a conscious or unconscious desire to suppress it. Some examples include Daylight Saving Time (that despite widespread dislike and evidence of negative impacts, the practice persists), Taboos (global poverty is a truth that is too heavy for our minds to constantly hold)… I won’t get too deep into this particular concept, you should read the book if you are interested.

One of the big differences on biological evolution to cultural is on how the transmission happens. Vertical transmission occurs when information (values, DNA…) is passed from parents to their children. Horizontal transmission happens among members of the same generation that are not direct family, and is much faster and flexible. Both kinds of evolution exhibit both kinds of transmission, but culture relies much more on horizontal and vice versa for bio.

Another good way of categorizing memetic information is by how the value it provides to humans change when it spreads. Memetic-invariant information remains constant in value if more people learn it (the sky is blue), memetic-cooperative information becomes more valuable if more people learn it (centralized fiat) and memetic-competitive information becomes less valuable if more people learn it (an undervalued asset). Most social media (and the broader information economy) exists to propagate memetic information. As memetic-competitive information is anti-memetic (no one wants to spread it, lest it loses value), it makes sense why it’s mostly filled with cooperative memes.

While memes might have certain amount of agency, it would be problematic to attribute moral value to them. We can however differentiate between Symbionts (memes that benefit their hosts, making them more likely to survive e.g. washing your hands) and Parasites (memes that harm their host but are effective at replicating).Parasitic memes are of particular interest, as being able to recognize them will help us to avoid them better. One of the keys lies in that they must endure the selection process while damaging their own hosts at the same time, which forces them to be really effective at replicating. This can apply both to a individual node and to the network, though those that are beneficial to the individual will be easier to spread.

This study traces the origin and development of the “Witch Hunt” meme during european prosecutions to answer the question: why did they persist and disseminate, despite the fact that no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? What they found was that the meme went through a Darwinian process, in which cultural variants of witchcraft beliefs accidentally triggered larger, more sensational, and more widespread persecutions, that were consequently better at spreading and replicating themselves.

The book heavily references The Elephant in the Brain and essays from both authors, Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson, both mentioned previously. The main idea of the book that humans often act with hidden motives, even from themselves, and that these motives are often related to self-interest, social status and signaling. This fits really nice with the concept of antimeme presented in the book, and helps explain how they emerged.

Our brains gently steer us toward narratives that makes us feel good, and away from those that don’t. When someone donates money to a charity, they tend to frame it as selfless altruism, rather than acknowledging motives like gaining power or assuaging guilt. These hidden, selfish motives are antimemetic: they remain invisible to the perceiver, because noticing them would present a challenge on how they see themselves. (page 75)

The Elephant in the brain is about one type of antimeme: selfish motives that threaten our self-image and social standing. But this same energy-preserving mechanism filters out any antimemetic idea that demands significant mental effort to process. (page 76)

While I enjoy both authors of The Elephant in the Brain, I find it that it relies a bit too much on anecdotal evidence scrambled together from all fields, which in turn does make it a good science communication book. The core idea has been discussed in much more detail in rationalist forums like LessWrong. The hostile telepaths problem presents a situation in which you’re dealing with a being (a) who can kind of read your internal experiences and (b) whom you don’t trust won’t make your situation worse due to what they find in you. This kind of situation easily explain the emergence of behaviors to deal with them. Even the controversial Ziz has some thoughts on the matter.

But antimemes can contain important information, so there is an interesting challenge in discerning the valuable ones and bringing them to the public eye. Here the author introduces the concepts of truth tellers and champions.

Truth-teller’s job is to air out our shared fears, doubts, and taboos to light. It has to know when an antimeme is ready for public consumption and how to present it in order to succeed. There have been people with this position since social learning emerged. Buffoons, oracles, shamans, tricksters, christian confession… all of these fulfill this role one way or another, and have proved vital to a proper cultural evolution. Even the occult and esoteric tradition, like Chaos magic, has it’s own word for memes, egregore 2.

Being shameless is not the same as truth-telling. The former is an act of self-interest for personal gain, while the latter is valued for it’s contribution to the collective interest. (page 96)

While the truth-teller surfaces antimemes into our collective consciousness, champions make sure that we keep paying attention to them, ensuring that these ideas are preserved and embedded into our institutions.

In a highly scaled and distributed marketplace of ideas, which issues we make progress on – the historic moments that come to define our story as a civilization – depends almost entirely on the quality of our champions.

Leslie A. White is an example of the truth-teller role (he described himself as the child pointing out the emperor is naked in the field of anthropology), with the publication ‘The Science of Culture: A Study of Man and Civilization’ (1949), where he introduced the term “culturology”. This was before the publications of The Selfish Gene, which would make Dawkins the undisputed champion is Dawkins of this example.

The book added more details and examples around these ideas, sometimes to their detriment, but I enjoyed them since most of them related to memes I have already been infected by. For example, it traces the surge of interest around a very specific type of meditation, called jhanas, and nails the chain of people that made this possible in my case (Qualia Research Institute → Nick Cammarata → Scott Alexander).

Attention is a precious, limited resource. We can’t expect to fully engage with every idea that enters our headspace. Yet at the same time, it’s clear that relying on unconscious filters can leave us blinded to opportunities that would otherwise be useful to see. (page 78)

Instead of trying to engineer a perfect hierarchy of attention, we should aim to cultivate a “biodiverse” information ecosystem (…) In biology, ecosystems with greater biodiversity are more resilient to shocks and better equipped to adapt to changing conditions (page 82)

As I briefly discussed in [consciousness is hard] the attention mechanism has a intricated relationship to consciousness. Our brain ingests enormous amounts of information every instant, but we are only conscious of a really small part, defining how we perceive the world. It is the bottleneck of the human brain, rather than computational power. The book discussed techniques like protocols and mnemonics as ways of optimizing our attention.

Risks

we are now living in what might be termed “late-stage memetic society” but “early-stage antimemetic society”: a patchwork of settlements that has opened it’s borders to refugees fleeing memetic contagion. (page 39)

This is one of the points where I disagree the most with the Nadia. We are not in late-stage memetic at all! There is a lot more to come!! AI will be extremely good at memetics (it already is), we are just starting to see internet capital markets being created, that allow for a much more close and immediate relationship from memetics to money, and the flow of information can still increase greatly before we get completely overwhelmed. In this section I will explore some of the dangers that I consider the most relevant for our future.

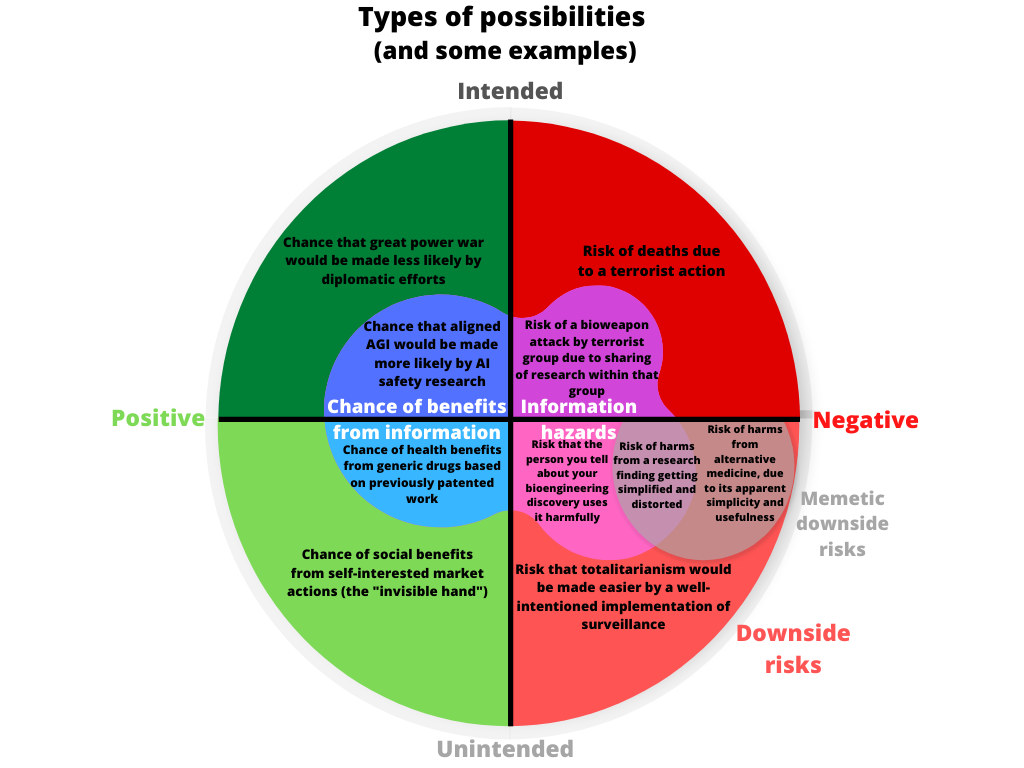

Memetic downside risks (MDRs) are defined as unintended negative effects that arise from how ideas evolve over time. They don’t necessarily need to be net negative, but its worth paying attention to them and mitigating if possible. Information hazards are risks that arise from the dissemination of true information that may enable some agent to cause harm (a subset of MDRs since those can be false as well). They come in many forms: data hazard, that contains specific content (eg. the blueprint to a nuclear bomb); attention hazard, where drawing of attention increases risk, even if the idea is already known); Neuropsychological hazards, where negative effects emerge from the particular ways in which our brains are structured; signaling hazard, template hazard… there are many others, that mostly rely on our biases and ignorance.

Information hazards are true by definition, but MDRs don’t have to be. For instance, compared to the claims of mainstream medicine, alternative medicine may seem simpler and more impressive. This might favor the selection pressure they experience and enable their short (relative) term spread.

Ideas will often evolve towards simplicity, salience, usefulness, and perceived usefulness, each a different selection pressure. This does not necessarily mean that they are turning worse, in fact most ideas have improved over time following this template. Simpler ideas will require less attention and are much easier to spread. Ideas that are more salient cause stronger emotions, thus making them easier to remember and share.

Usefulness is a bit more complicated since it depends on the node’s perspective. Adaptation in this direction can be expected to be beneficial in most cases, but not always. For example, selection pressures over social signalling might help explain the increase on political polarization. Perceived usefulness happens when an idea isn’t actually better than others, but it appears as such. The easier it is to assess the true usefulness of an idea, the less this will apply. Ideas that rely too much on this tend to deteriorate the network.

There also exists a tendency for ideas to become noisier over time, in which random mutations are constantly modifying it, usually correlated to the amount of nodes it’s spread over. This already happens in genes, where genetic drift is the process by which random change influences the frequency of gene variants in a population (mutation without selection). It’s particularly relevant on small populations and can lead to loss of genetic diversity.

The phenomenon of “memetic drift4” seems to be one of Robin Hanson’s latest interests, as he worries that these small, cumulative changes can, over time, erode important cultural values and traditions with consequences for social stability. In the past, when cultures were under strong selection pressures, maladaptive changes were usually weeded out. In the modern era, cultural change is much faster and there is less diversity, which propitiates dysfunctions.

Fertility is possibly the clearest example, where he argues that recent decreases are a result of memes that encourage people to focus on meme propagation (social influence, status…) rather than genetic reproduction, which in turn could lead to our extinction. The other big risk he identifies is the loss of diversity and surge of a global “monoculture”, that would make societies more fragile and susceptible to large-scale negative shifts in values and behavior. Corporate and romantic cultures seem to suffer from the same problem, where the lack of error-correction mechanisms makes them degrade over time.

Proposed fixes include a conservative return, in which we adopt values proved by time; totalitarian cultural control or deep multiculturalism. The reason why diversity could solve this is that evolution between species is more important (more adaptive) than evolution within species, both in cultural and bio evolution. A problem with Hanson’s argument is that it relies on your perspective on current culture, while if it’s the true that it has maladapted, it makes sense for it to disappear. Surprisingly this does not happen as much on memes related to science, math or technology, presumably because interests of memes and genes are aligned in these fields, whereas in values they can be opposed.

Clown attacks are a tactic based on the fact that perception of social status affects what thoughts the human brain is and isn’t willing to think. State agencies are the ones that take the most advantage of this. By exploiting the human tendency to associate specific ideas with low social status, it will inhibit the human brain from pursuing that targeted line of thought. Examples include conspiracy theories being the main people who are seen talking about the Snowden revelation or right-wing clowns defending nuclear energy. They are difficult to handle because you’ll worry that, by entertaining that line of thought, you will lose status in the eyes of other people.

That is one particular kind of attack, but we know that the human brain is a amalgamation of spaghetti code and that it has exploits. The things is, you don’t really need to understand the whole system in order to make use of them. If we think of social media as a controlled environment for automated experimentation, with a extremely low cost to collect massive amounts of human behavior data, finding complex social engineering techniques is the kind of task where machine learning excels at. These vulnerabilities are not particularly well-hidden.

Supermemes, as defined by memes that contain high impact information with high transmissibility are also risky, mainly because of their scale. Early forms of religions like Judaism and Islam were “highly virulent” and infected big swaths of population, probably because it was a beneficial adaptation at the time. But,

when supermemes lack clear focus on specific outcomes, they can trap people in a state of perma-crisis that never fully escalates or resolves. (page 69)

Got people close to me that live like this, particularly worrying about immigration and demographics, and while those are perfectly valid problems, the amount of attention that it takes out of their daily lives makes this comparable to living with some illness like long-covid.

Propaganda is basically a memetic hazard on a national scale, and cognitive warfare / hybrid warfare has been a field in geopolitics for quite some time now.

Memetics have an interesting relationship to LLMs, since one of language’s main roles is the transmission of meme. The recent phenomenon of LLM induce psychosis seems quite relevant, as it points to the extreme competence that these AIs have in the manipulation and transmission of memes. AI alignment research would probably benefit from more attention to this lens.

As I argued in Mental illnesses and the Looping Effect, our psychology is increasingly being affected by what, in essence, are memetic attacks that evolution has adapted us to respond a certain way. Major traumatic events like genocides result in memes that carry the wounds and the coping strategies of whole communities. Some addictions are really strong memes that refuse to leave the host.

Prevention

One obvious idea is just to use your reason to differentiate between the good and bad memes an ignore the bad ones. For one, you can’t just ignore a meme, and rationality can sometimes serve as a “memetic immune disorder”, meaning that over-rationality can remove cultural antibodies, evolved against certain memes that might seem illogical. Listening to your emotional responses can help against this, we have a memetic immune system developed as the product of meme-gene coevolution that is actually quite good.

Some things you can do is start considering that some information environments might be adversarial (like hyper optimized impression hacking environments), minimize exposure to sensors (open webcams, avoid sleeping in the same room as a smart device…) end being more cautious about “low-fidelity” methods of spreading ideas (mass media, X…). Take into account that some downside risk might take more effort to prevent than the damage they do

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy can be thought of as a form of applied antimemetics. A person’s cognitive distortions (“I am worthless,” “Everyone is against me”) are antimemetic since they are painful to confront. A therapist acts as a private “truth-teller” in this context.

Future Directions

I think AI might bring a bit of a revival to memetics. It allows for quantitative analysis of all kind of data that was completely inaccessible before. There are many technologies that become available after this. Computer modeling of memetics was a dead end for many years, but the availability of embeddings and multimodal changes this.

By studying previous memes with new tools, we can use to test against our predictions. Meme extinction events are interesting as well, and meme paleontology sounds like a real job to me in a couple years. Some people are already working on this.

Crypto is maybe the industry that has the deepest understanding of memes, at least in their particular context. Meme tokens are literally financialized memetics, with people betting money on the memetic value of a particular image and letter combination. Funnily enough, research point to a “strong positive association between meme activities and negative earnings ” in traditional stocks. I expect this to reverse as internet capital markets become more accessible.

This is about it for now, I wrote this in 4 frantic days while in vacation at Barcelona. As it keeps happenning, at about 75% of completeness of a project I loose interest, making my texts unstructured and and unpleasant to follow. My other big problem is that I tend to compress information too much in text, making important ideas difficult to differentiate from the rest. Anyway, thanks to pedro and niko for feeding me, giving me a place to stay and generally taking care of me during the this time.

More Resources

I encourage the reader to follow the link in the post, as the value of my content is more of curation rather than writing. In fact few ideas in here are really mine, but I enyojed exploring them.

-

nosilverv is going to publish a book related to memetics soon.

-

Can you eliminate memetic scarcity, instead of fighting? — LessWrong

-

Tim Tyler - Memetics: Memes and the Science of Cultural Evolution

-

wearehostsformemes/meta-meme.txt at master · lupuleasa-core/wearehostsformemes · GitHub

-

Why Care About Meme Hazards and Thoughts on How to Handle Them | Qualia Computing

Todo maybe

connect with free energy principle in the brain ??

memetic entropy as they evolve over time ?

Regarding the Pain of Others by Susan Sontag | Goodreads tried to memetic photography war and failed

Footnotes

-

In particular, the enormous increase of the free flow of information (and thus memes) permitted by the internet and globalization. ↩

-

I intended on writing a post on chaos magick and failed miserably. I took it as seriously as I could but I’m already quite bad at interpreting symbols in my daily life, so it was really difficult for me to find footing. Hopefully I’ll pick it back up at some point as it is a surprisingly deep field. ↩ ↩2

-

Without getting too deep into this, quoting this LessWrong post: > We’re already in the timeline where the research and manipulation of the human thought process is widespread; SOTA psychological research systems require massive amounts of human behavior data, which in turn requires massive numbers of unsuspecting test subjects (users) in order to automate the process of analyzing and exploiting human targets. This therefore must happen covertly, and both the US and China have a strong track record of doing things like this. This outcome is a strong attractor state since anyone with enough data can do it, and it naturally follows that powerful organizations would deny others access e.g. via data poisoning. ↩

-

“Cultural drift” is kind of a synonym, referring more to memetic drift in population. ↩